James David Griffiths and Stuart Perrett

The 2024 UK General Election is upon us and the British Election Study team has produced the 2024 Election Provisional Panel Dataset, which includes data from Wave 26 (May 2024). In this blog, the team provides some initial insights on how this dataset can help us understand British politics ahead of July 4th. Our first insight is that, while the Conservatives’ support has fallen across Britain, this has not entirely reversed some of the key patterns that were clear in 2019 (yet).

When the Conservatives won their 80-seat majority in 2019, few could have foreseen the period that they would preside over. A global pandemic, a cost-of-living crisis, and two changes of Prime Minister – among other things – have made this a uniquely turbulent time in British politics. Given all that has happened, this is an ideal moment to examine how politics has changed since the last election.

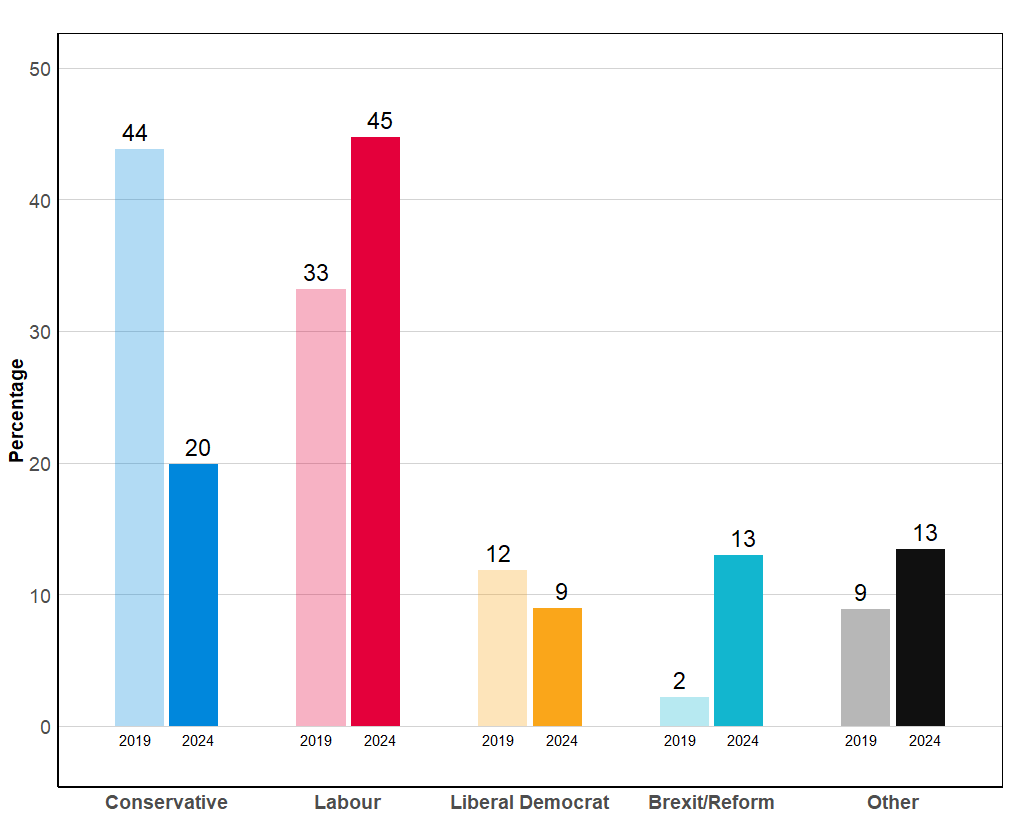

Ultimately, the biggest electoral change since 2019 can be seen in Conservative support. While the Tories won 44 percent in the last election, they now find their vote has fallen by over half to around 20 percent in May 2024 (Figure 1). The data in this wave were collected before the 2024 election was announced, but more recent polling suggests that the Conservatives are still languishing at a similar level. Other parties have also experienced changes in their vote, with Labour rising 12 percentage points and Reform UK now polling at a similar rate to UKIP’s vote share in 2015, but these changes are smaller compared to the Conservatives’ change in fortunes.

Figure 1: Vote in 2019 and vote intention in May 2024 in Britain

Source: British Election Study 2024 Election Provisional Panel Dataset

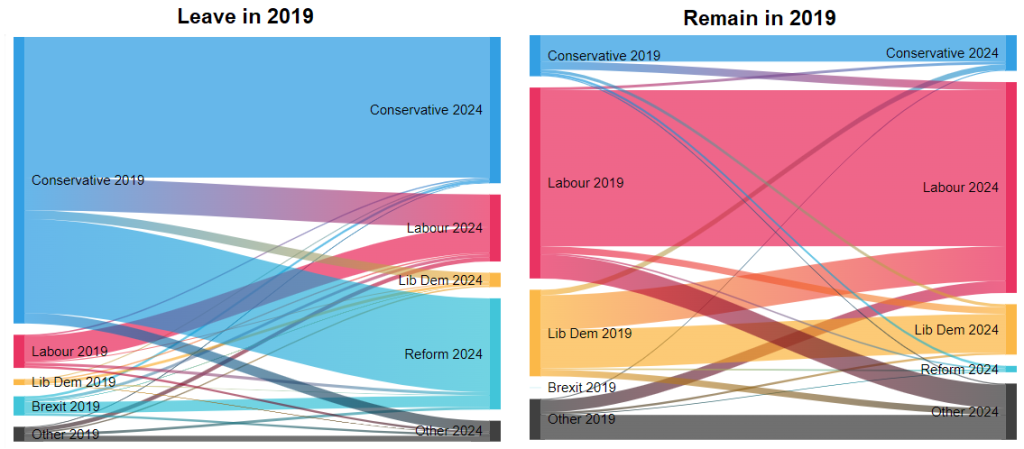

So, where have these voters gone? Ultimately, patterns of vote switching tend to depend on Brexit preferences (Figure 2), despite the fact it is no longer a salient issue for most voters. While the Conservatives won the overwhelming majority of those who supported Brexit in 2019, they now command the support of only 40 percent of those who support it in 2024 (when excluding non-voters/don’t knows). Many Leave voters have switched to Labour, but the bulk have moved towards Reform, meaning 72 percent of Leave voters still back a pro-Brexit party. In contrast, Labour have consolidated their position among those who opposed Brexit in 2019, retaining most of their vote – including attracting support from a considerable chunk of those who previously voted for the Liberal Democrats ahead of the election announcement.

Figure 2: Flows of vote between 2019 and 2024 by Brexit

Using the profile variable for 2019 vote, Brexit support in 2019, and cross-sectional May 2024 weights. Excludes non-voters, those who said that they wouldn’t vote, and don’t knows.

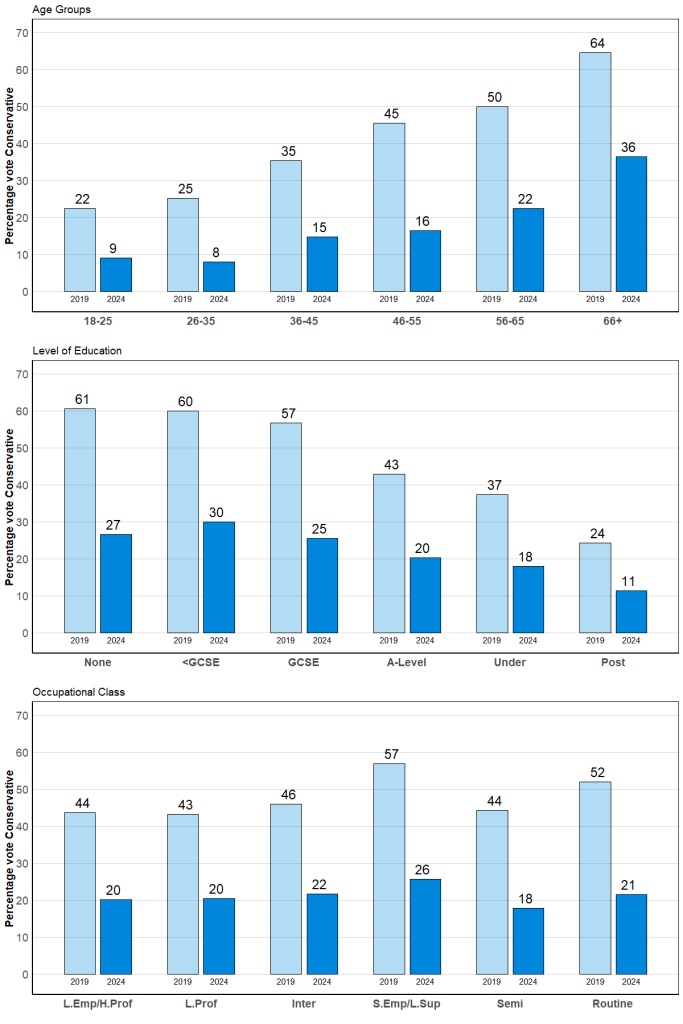

The persistence of these Brexit-based splits in vote reflects how the the patterns of support underpinning British politics are still similar to what they were in 2019, despite the Conservatives’ drop in support. The Tories’ victory in 2019 reflected growing age and education divides in Conservative/Labour support, and a decline in class-based differences in voting, and their losses are yet to reverse these trends entirely. In Figure 3 we plot the Conservative support by age, education, and occupational class, excluding don’t know/non-voters. It is clear that the pattern of support among these three important demographic groups is similar in 2019 and 2024, even if the overall level of Conservative support is lower ahead of this election. Simply put, older voters and those without a university degree are still more likely to support the Conservatives than younger and university-educated voters. The relative differences have shrunk, as Conservative support has fallen furthest where it was strongest in 2019, but overall the patterns persist for now. Similarly, we do not observe class differences in Conservative support in 2024, which echoes the results from 2019. In this sense, the realignments of the past decade are persisting even though Conservative support is falling overall.

Figure 3: Vote in 2019 and vote intention in May 2024 by age, education, and class

Source: British Election Study 2024 Election Provisional Dataset. Excludes non-voters, those who said that they wouldn’t vote, and don’t knows.

That said, even as Brexit continues to structure politics under the surface, it is important to note that attitudes towards Europe have changed since 2019. In Figure 4, we look at vote intention in a prospective EU referendum, including those who wouldn’t vote or don’t know. Overall, we find that the proportion of people supporting Brexit has declined since 2019, falling from 41 percent who wanted to leave in 2019 to around 34 percent who want to stay out in 2024. This is notable because the Conservatives still rely heavily on pro-Brexit voters, who made up 82 percent of their supporters in 2019 and 70 percent in 2024.

In contrast, around 50 percent of Britain would like to Rejoin the EU, even when accounting for those who are unsure of their position. This is important for Labour’s support, as their voters are overwhelmingly anti-Brexit (81 percent in 2019, 76 percent in 2024). One explanation for this shift is that some of those 2019 Leavers who have switched from the Conservatives to Labour or the Liberal Democrats have also changed their position on Brexit (36 percent of Con to Lab/LD switchers who backed Leave in 2019 do not support Brexit in 2024 – either because they want to re-join the EU, would not vote, or don’t know), but another is that, given the age profile of Brexit supporters, many of these voters are no longer in the electorate.

Figure 4: Vote in a prospective EU Referendum between 2019 and 2024

Wording: Remain/Leave in 2019, Re-join/Stay-out from 2020.

These analyses of Wave 26 of the British Election Study’s panel series demonstrate the difficult position that the Conservatives found themselves in going into the campaign, as it appears that their vote share in the upcoming election will halve. At the same time, their struggles have not changed the underlying structure of British politics, yet. The demographic realignments that were so key in 2019 persist, indicating that the legacy of Brexit continues to shape vote choice – even as opinion on Europe shifts. Consequently, the Conservatives find themselves tied to a section of the electorate that is shrinking, as well as splitting away from them. In this political context – of continuity and change – panel data from the British Election Study data can provide unique insights for researchers moving forward.