We’re all Disillusioned: Age and Political Disaffection in the 2024 UK General Election

Jane Green and Marie-Lou Sohnius

Nuffield Politics Research Centre, Nuffield College, University of Oxford

Elections can acquire a label, remembered as such in history. 2019 was, for example, ‘The Brexit Election’. 2024 was, we suggest, ‘The Disillusionment Election’.

This has implications for how we think of the problems of disaffection among young people. That has tended, in recent elections, to be a particular problem in terms of lower turnout among the young, but what about when there was much lower turnout overall (at 59.7%) and high disaffection across the board?

We analysed two forms of disillusionment in the British Election Study (BES) internet panel – feelings that political parties ‘don’t care what people like me think’ (a measure of political efficacy), asked before the 4th July General Election, and perceptions that political parties ‘look after the interests of’ different groups, asked after the election.

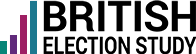

According to our BES analysis, the youngest group of voters (18 – 29s) were not, perhaps surprisingly, the most disaffected in 2024, measured using our political efficacy question; they were accompanied by respondents aged between 30 and 60. Around three-quarters of all under 60s had high levels of disaffection in 2024 (or low levels of ‘personal political efficacy’), with similar levels among the under 30s, under 45s, and under 60s, as Figure 1 shows, below.

Figure 1: Proportion of BES internet panel respondents (pre-election) agreeing that ‘politicians don’t care what people like me think’ by age group, May-June 2024

The BES survey asked respondents whether each of the competitive parties ‘looks after the interests of’ different groups (Conservatives, Labour, Lib Dems, Greens, Reform UK, SNP in Scotland and Plaid Cymru in Wales). The perception of at least some representation of one’s own group is more positive, when respondents are comparing the representation of different groups for each party in turn.

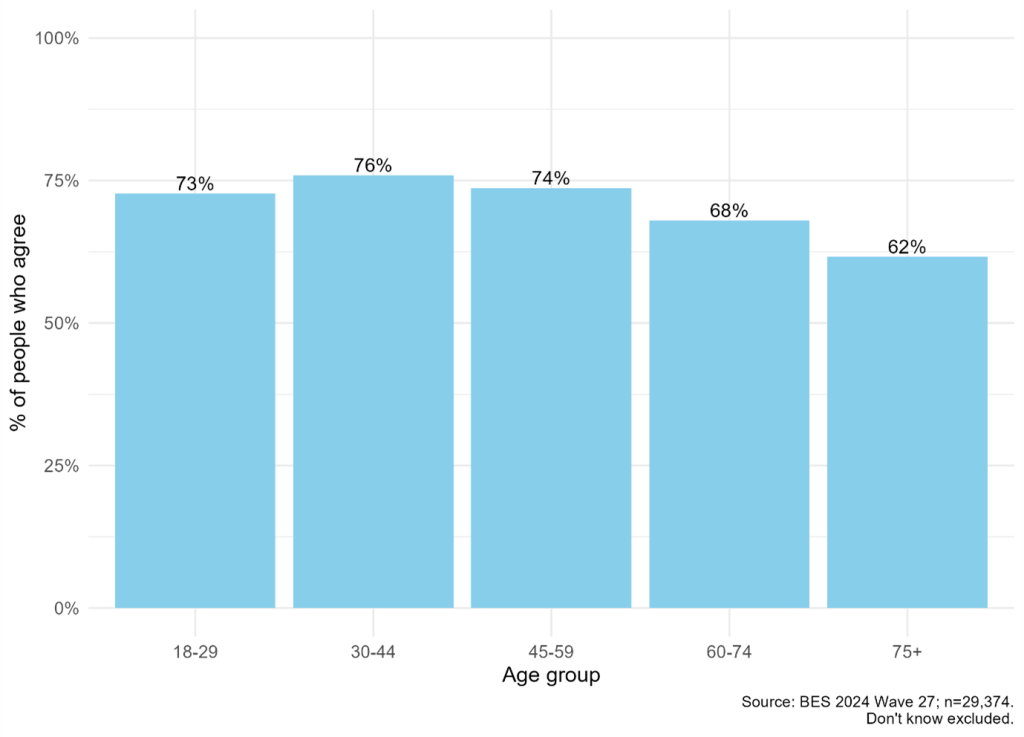

We calculated whether a respondent agreed that any of those parties ‘looks after the interests of’ the group to which we could assign them, based on their response to their social class identification, age, ethnicity, and whether the respondent was retired.

The vast majority (87%) of the under 30s thought that at least one of those parties ‘looks after the interests of’ the young. The equivalent figure (for each group) was lower among ethnic minorities (76% of ethnic minorities thought that at least one party looks after the interests of black and Asian people), and retirees (79% of retired respondents in the sample thought at least one party looks after the interests of the retired). The group that felt most represented by any party in 2024 was those who identified as middle-class, followed by those who identified as working class.

We can see here, in Figure 2, that the under 30s were by no means alone in their overall assessment that at least one party looks after the interests of ‘their’ group (note, we are not implying here that all members of a group feel that group identity or membership equally, or at all – this is simply a way of classifying likely group self-identification).

Figure 2: Proportions of BES internet panel respondents (post-election) agreeing that any party ‘cares about the interests’ of ‘their’ group, July 2024

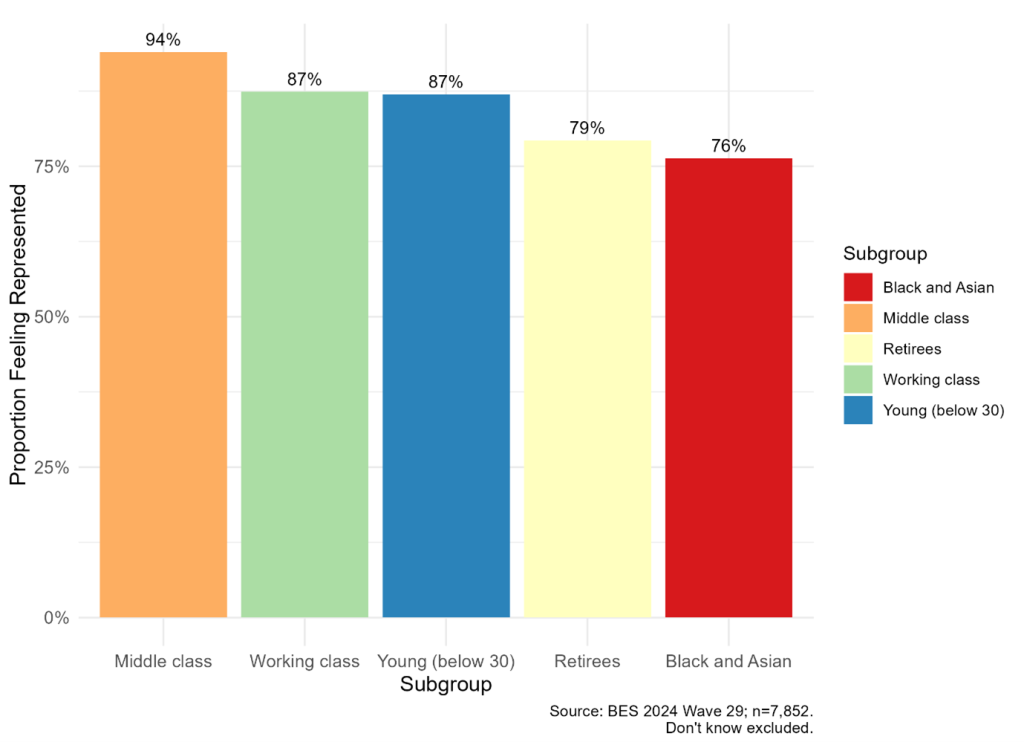

However, for the young, the perception that at least one party represents the interests of the young is because the largest proportion (62%) saw the Greens as looking after the interests of the young, closely followed by Labour (59%), who of course only won the election in 2024.

Figure 3 shows these proportions.

Figure 3: Proportions of BES internet panel respondents under 30 agreeing that each party ‘looks after the interests’ of young people, July 2024

While the Greens got their highest ever seat tally in the 2024 general election (four MPs), they cannot, currently, represent young people’s interests as part of a government in Westminster. And Labour, who have now formed a government, were of course in opposition for fourteen years.

We examined reported turnout and found that the youngest group was 20 points less likely to have reported a vote in 2024 than the 75+ group. BES data suggests that the age-turnout gradient was slightly less steep at the lower ages in 2024, but this is reported turnout that needs to be verified later with random probability BES data.

So, young people felt better represented, up to 2024, by parties that could not deliver for them in government. Most damning for the outgoing governing party is that only 12% of under 30s thought that the Conservatives look after the interests of young people in July 2024. That’s lower than for Reform UK (22%), and it is not surprising, given the tenor and focus of the Conservative 2024 campaign, which included a policy proposal of national service for 18-year-olds and a focus on preserving pensions.

Perhaps, with the Labour Party now in government, some representation in Parliament of the Greens, and an increase in Lib Dem MPs, young people may feel more politically represented. However, that will largely depend on Labour’s ability to make specific appeals – symbolic or policy commitments – that resonate with young voters.