James Griffiths and Stuart Perrett

The British Election Study team explores how the circumstances heading into the 2024 UK General Election compare to the that of the last three elections.

Recent results from the BES 2024 Provisional Election Panel Dataset demonstrate that the Conservatives have lost considerable support, which raises an important question – why are voters turning away from the party? Using the same data, we argue that strong public dissatisfaction ahead of the election is particularly difficult for an incumbent – and the Conservatives are not the only governing party that is suffering.[1]

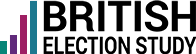

First and foremost, British voters are unhappy about the condition of the nation. For example, the public are more negative about the performance of the economy and the NHS than they were before any previous election since the Conservatives entered office in 2010 (Figure 1). Voters became increasingly dissatisfied with the economy at each election during this period, but 2024 is unique in that there are considerably more people with very negative views, and this is also the case for opinion on the NHS. Given that these are some of the issues that voters care about the most, this sentiment will pose a difficult challenge for the Conservative Party – indeed, such dissatisfaction would be challenging for any incumbent to overcome.

Figure 1: Pre-election percentages of those who feel the economy and the NHS has got a little/lot worse ahead of the election in 2015, 2017, 2019, and 2024 (Source: British Election Study 2024 Election Provisional Panel Dataset)

Given the difficulties facing Britain, it may be no surprise that the public are particularly critical of the Conservative government ahead of this election (Figure 2). Strong disapproval of the UK Government is at its highest pre-election level since the Conservatives took office, with the increase being particularly pronounced in England and Wales. Such criticisms reflect worsening perceptions about the Government’s handling of the cost of living crisis, the pandemic, and – before that – the austerity of the 2010’s. Since the Conservative Party have been in power for 14 consecutive years, voters are more likely to hold the party responsible for these perceptions.

However, the Conservatives are not alone in facing the wrath of the public; disapproval of incumbent Scottish and Welsh governments are also higher than before any recent General Election. This may well explain the SNP’sstruggles in Scotland. Interestingly, Labour are polling well in Wales despite heavy criticism of their performance in the Senedd – suggesting that voters may be treating these two levels of Government separately.

Figure 2: Pre-election percentages of those who disapprove of the UK, Scottish, and Welsh governments in England, Scotland, and Wales in 2015, 2017, 2019, and 2024 (Source: British Election Study 2024 Election Provisional Panel Dataset)

Dissatisfaction with Government performance represents one form of voter negativity. There is also evidence of a more general form of political alienation. When tracking trust in Members of Parliament, we find that this is at its lowest pre-election level recorded in the BES Internet Panel (Figure 3). Overall, the proportion of those saying that they have “no trust” in politicians has increased from 16 percent in 2015 to 35 percent in 2024. On the one hand, this indicates a growing frustration with the political system. However, it is also true that political trust is associated with government approval, so it may be that these lower levels of trust are a reflection of dissatisfaction with the current incumbents – which is something for future research to explore with BES data!

Figure 3: Pre-election mean level of trust in MPs in 2015, 2017, 2019, and 2024 (Source: British Election Study 2024 Election Provisional Panel Dataset)

Taking dissatisfaction and disaffection together helps us understand why Labour had a considerable lead over the Conservatives heading into this election. However, it is important to note that Labour’s large lead does not reflect an abnormally high level of enthusiasm for the party (Figure 4). Though like scores for Labour are, on average, higher than in 2019, they are slightly lower than they were in both 2015 and 2017. What is clearly unique compared to previous elections is the scale of the drop in Conservative support. Simply put, it is Labour’s relative popularity that will matter in the first past the post system – rather than it’s absolute level of popularity.

Figure 4: Pre-election mean like/dislike ratings of Conservatives and Labour in MPs in 2015, 2017, 2019, and 2024 (Source: British Election Study 2024 Election Provisional Panel Dataset)

Overall, the Conservatives began the election campaign in an uneviable position, with disapproval of their performance on the economy and the NHS higher than it has been ahead of previous elections. Such dissaproval is a strong predictor of vote switching, and has likely contributed to the low level of support they currently hold. However, voters are also dissatisfied with devolved incumbents and increasingly sceptical of politicians in a more general sense. How such political apathy evolves and interacts with government dissatification and party support – especially if the next General Election puts a new party in power – remains to be seen.

[1] We stress that our 2024 data is not strictly from a pre-election wave, as data collection finished before the election was announced. That said, we do not anticipate that any of our variables in this piece (economic perspectives, government approval, trust, party likes) will be influenced by the announcement, so we believe that our analysis is comparable with other pre-election waves.